Absurdities Part-2: From Handle to Object

Introduction

In my ongoing effort to step outside my comfort zone, I decided to take on the challenge of Windows Internals reverse engineering since it’s a long ago I’ve been working with this stuff.

My curiosity was first sparked by Adam Chester - OpenProcess filtering which explores how the AVG engine restricts debugger access via the OpenProcess function. That led me to another excellent resource: Sina Karvandi - Reversing Windows Internals, which dives into the inner workings of the PsOpenProcess function.

Inspired by these works, I decided to reverse-engineer PsOpenProcess myself to understand how it operates—then push further by analyzing how an antivirus driver uses this function to filter handle access and block debuggers.

☠️ ATTENTION ☠️

You'll see phrases like "maybe", "I think", or "I believe" scattered throughout this post — and that's not poor writing, it's just the reality of reversing undocumented Windows internals. Strap in, it's gonna be a fun trip.

Analysis was done on Windows 11, version 24H2 (build 26100.4652), and Kaspersky Endpoint Security 12.10.0.466

What is a handle?

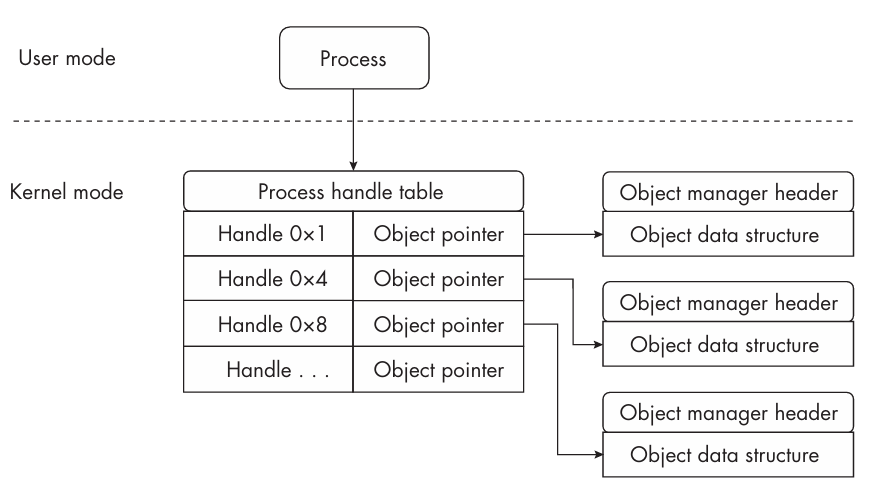

Windows is an object-based operating system, meaning that nearly everything — files, processes, threads, registry keys — is represented as an object. To access these objects, Windows uses handles, which are unique identifiers associated with a specific object.

In the case of process objects, each handle is stored in a structure known as the handle table. This table maps handle values to internal pointers that reference the actual kernel objects.

Every process in Windows has its own handle table, located within the process’s _EPROCESS structure in kernel memory. This structure contains numerous important fields, including the process ID, a pointer to the PEB (Process Environment Block), and the handle table itself.

kd> dt nt!_EPROCESS

+0x000 Pcb : _KPROCESS

+0x1c8 ProcessLock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

........

+0x2e0 Peb : Ptr64 _PEB

+0x2e8 Session : Ptr64 _PSP_SESSION_SPACE

+0x2f0 Spare1 : Ptr64 Void

+0x2f8 QuotaBlock : Ptr64 _EPROCESS_QUOTA_BLOCK

+0x300 ObjectTable : Ptr64 _HANDLE_TABLE // -> _HANDLE_TABLE

........

All handles within a process are organized through a doubly linked list managed by the _HANDLE_TABLE structure. This structure contains an array of _HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY structures, which is based on TableCode field.

Each handle value is actually an index inside that array (TableCode + HandleValue*4 -> Handle Entry Address)

kd> dt nt!_HANDLE_TABLE 0xffffc98d`ce0c7e40

+0x000 NextHandleNeedingPool : 0x400

+0x004 ExtraInfoPages : 0n0

+0x008 TableCode : 0xffffc98d`ce9ff000 // -> Array of Handle Table Entries

+0x010 QuotaProcess : 0xffff8a82`2dfc8080 _EPROCESS

+0x018 HandleTableList : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0xffffc98d`ce0c6558 - 0xffffc98d`ce0c63d8 ]

+0x028 UniqueProcessId : 0x2264

+0x02c Flags : 0

+0x02c StrictFIFO : 0y0

+0x02c EnableHandleExceptions : 0y0

+0x02c Rundown : 0y0

+0x02c Duplicated : 0y0

+0x02c RaiseUMExceptionOnInvalidHandleClose : 0y0

+0x030 HandleContentionEvent : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x038 HandleTableLock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x040 FreeLists : [1] _HANDLE_TABLE_FREE_LIST

+0x040 ActualEntry : [32] ""

+0x060 DebugInfo : (null)

kd> dq 0xffffc98d`ce9ff000

ffffc98d`ce9ff000 00000000`00000000 00000000`00000000 // -> Reserved

ffffc98d`ce9ff010 8a822d48`d330fff5 00000000`001f0003

ffffc98d`ce9ff020 8a822d48`d7b0ffed 00000000`001f0003

ffffc98d`ce9ff030 8a822dca`9dd0ffeb 00000000`00000001

ffffc98d`ce9ff040 8a822e26`a490ffcf 00000000`001f0003

ffffc98d`ce9ff050 8a822dd1`cd40ffa1 00000000`000f00ff

ffffc98d`ce9ff060 8a822d4d`9c90fff5 00000000`00100002

ffffc98d`ce9ff070 8a822dca`aee0fff9 00000000`00000001

kd> dt nt!_HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY ffffc98d`ce9ff010

+0x000 VolatileLowValue : 0n-8466154558699012107

+0x000 LowValue : 0n-8466154558699012107

+0x000 InfoTable : 0x8a822d48`d330fff5 _HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY_INFO

+0x008 HighValue : 0n2031619

+0x008 NextFreeHandleEntry : 0x00000000`001f0003 _HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY

+0x008 LeafHandleValue : _EXHANDLE

+0x000 RefCountField : 0n-8466154558699012107

+0x000 Unlocked : 0y1

+0x000 RefCnt : 0y0111111111111010 (0x7ffa)

+0x000 Attributes : 0y000

+0x000 ObjectPointerBits : 0y10001010100000100010110101001000110100110011 (0x8a822d48d33)

+0x008 GrantedAccessBits : 0y0000111110000000000000011 (0x1f0003)

+0x008 NoRightsUpgrade : 0y0

+0x008 Spare1 : 0y000000 (0)

+0x00c Spare2 : 0

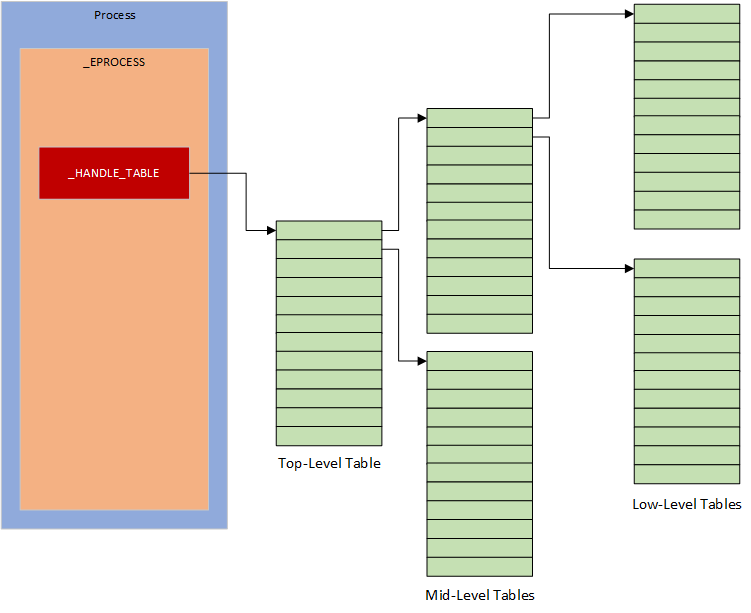

Each table is initialized using the undocumented function ExpAllocateTablePagedPool, which allocates a page of memory and sets up the initial table structure. Since each page is 4096 bytes and each handle entry is 16 bytes, this only allows space for 256 entries (4096 / 16 = 256). Obviously, this isn’t enough for processes that require more handles.

To scale beyond this limit, Windows uses a three-level table structure to dynamically manage handle entries:

- Top-Level Table

- Holds up to 256 pointers to Mid-Level Tables.

- Each pointer is initialized only when needed, to save memory.

- Mid-Level Tables

- Each contains 256 pointers to Low-Level Tables.

- Low-Level Tables

- These are the actual memory pages that store handle entries, each 16 bytes in size.

Of course, Windows does not allocate all levels of the handle table during process creation — doing so would waste memory. Instead, these tables are allocated on-demand when a process begins creating handles. This is handled by internal routines such as:

ExpAllocateMiddleLevelTableExpAllocateLowLevelTableExpAllocateTablePagedPool- called by ExCreateHandleTable/ExDupHandleTable depending on if the parent_EPROCESSis passed to ObInitProcess or not. For more details, see am0nsec - Journey Into the Object Manager Executive Subsystem.

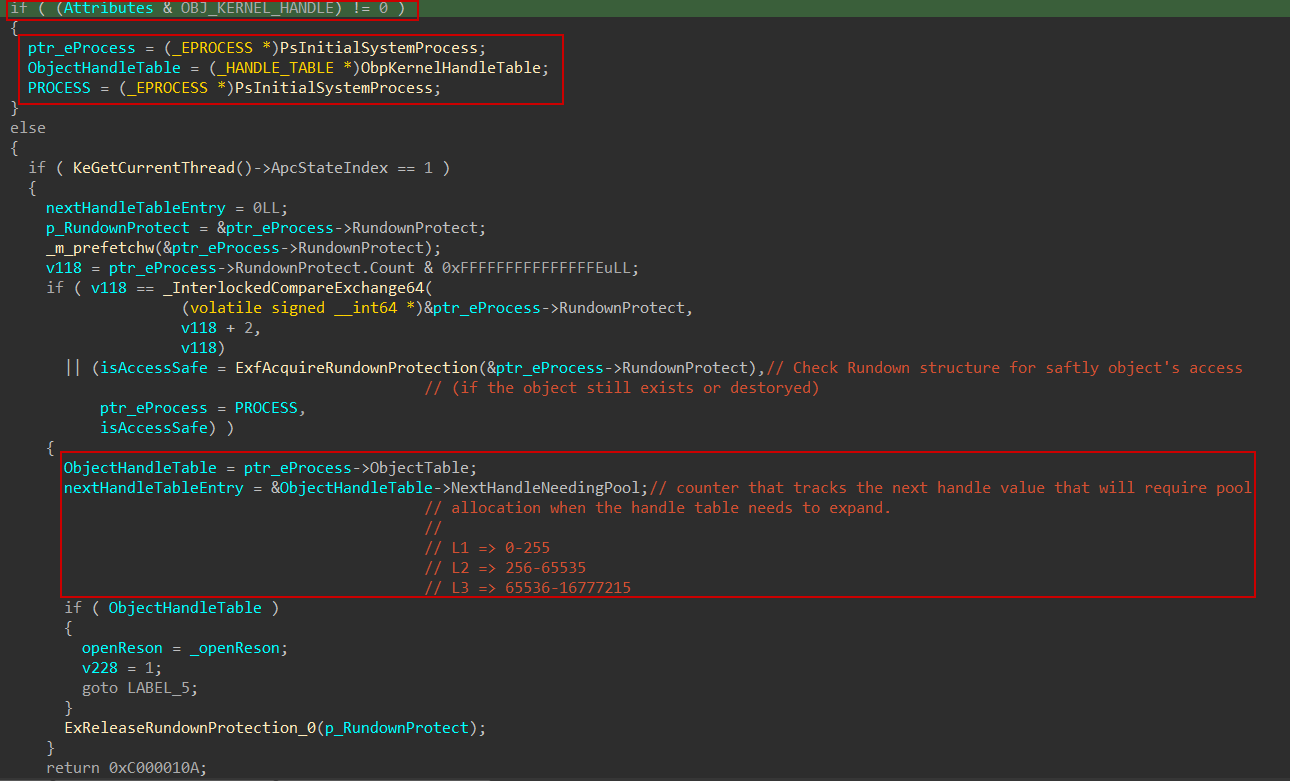

To keep track of which level needs to be allocated next, Windows uses the internal field NextHandleNeedingPool inside the _HANDLE_TABLE structure which I believe that it maps to different handle index ranges across the three levels:

L1: 0 – 255

L2: 256 – 65,535

L3: 65,536 – 16,777,215

What is an Object?

An object is a data structure that represents a system resource, such as a file, thread, or graphic image. According to MSDN: object-categories, there are 3 main categories of objects:

- User Objects

- GDI Objects

- Kernel Objects

Each object has a header of _OBJECT_HEADER structure which contains the object’s type, handle count, and other metadata about that object. Each header is allocated just before the actual object by offset of 0x30 bytes.

We can get the _EPROCESS addresses of all running processes using !dml_proc command and then we can get the _OBJECT_HEADER address of each process by subtracting 0x30 (the size of the _OBJECT_HEADER structure) bytes from the _EPROCESS address.

kd> !dml_proc

Address PID Image file name

ffffd285`816a8040 4 System

ffffd285`816a6080 7c Registry

ffffd285`85479080 20c smss.exe

ffffd285`85cd9140 2d4 csrss.exe

ffffd285`860d2080 324 wininit.exe

ffffd285`860ea140 32c csrss.exe

ffffd285`86154080 37c winlogon.exe

ffffd285`86189080 3c0 services.exe

ffffd285`8618f080 3d4 lsass.exe

ffffd285`85de2240 1ec svchost.exe

ffffd285`86267140 404 fontdrvhost.ex

ffffd285`86265140 290 fontdrvhost.ex

ffffd285`86164080 458 svchost.exe

ffffd285`8616b240 490 svchost.exe

ffffd285`8642c080 4d8 dwm.exe

.......................

ffffd285`8cfb60c0 12b0 Notepad.exe

kd> dt nt!_OBJECT_HEADER ffffd285`8cfb60c0-0x30

+0x000 PointerCount : 0n361582

+0x008 HandleCount : 0n12

+0x008 NextToFree : 0x00000000`0000000c Void

+0x010 Lock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x018 TypeIndex : 0xa6 ''

+0x019 TraceFlags : 0 ''

+0x019 DbgRefTrace : 0y0

+0x019 DbgTracePermanent : 0y0

+0x01a InfoMask : 0x88 ''

+0x01b Flags : 0 ''

+0x01b NewObject : 0y0

+0x01b KernelObject : 0y0

+0x01b KernelOnlyAccess : 0y0

+0x01b ExclusiveObject : 0y0

+0x01b PermanentObject : 0y0

+0x01b DefaultSecurityQuota : 0y0

+0x01b SingleHandleEntry : 0y0

+0x01b DeletedInline : 0y0

+0x01c Reserved : 0

+0x020 ObjectCreateInfo : 0xfffff800`e7827bc0 _OBJECT_CREATE_INFORMATION

+0x020 QuotaBlockCharged : 0xfffff800`e7827bc0 Void

+0x028 SecurityDescriptor : 0xffffe68a`cb7dbbaf Void

+0x030 Body : _QUAD

We can get also the type of that object extracted from another structure called _OBJECT_TYPE. at offset 0x10 of the _OBJECT_TYPE structure, we can find the name of the object type (e.g. Process, Thread, File, etc.).

kd> !object ffffd285`8cfb60c0

Object: ffffd2858cfb60c0 Type: (ffffd285816ab3f0) Process

ObjectHeader: ffffd2858cfb6090 (new version)

HandleCount: 12 PointerCount: 361582

kd> dt nt!_OBJECT_TYPE ffffd285816ab3f0

+0x000 TypeList : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0xffffd285`816ab3f0 - 0xffffd285`816ab3f0 ]

+0x010 Name : _UNICODE_STRING "Process"

+0x020 DefaultObject : (null)

+0x028 Index : 0x8 ''

+0x02c TotalNumberOfObjects : 0xd3

+0x030 TotalNumberOfHandles : 0x8c2

+0x034 HighWaterNumberOfObjects : 0x1a9

+0x038 HighWaterNumberOfHandles : 0xa92

+0x040 TypeInfo : _OBJECT_TYPE_INITIALIZER

+0x0b8 TypeLock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x0c0 Key : 0x636f7250

+0x0c8 CallbackList : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0xffffe68a`c38ffc30 - 0xffffe68a`c39fbf20 ]

+0x0d8 SeMandatoryLabelMask : 3

+0x0dc SeTrustConstraintMask : 0

PsOpenProcess Under the Hood

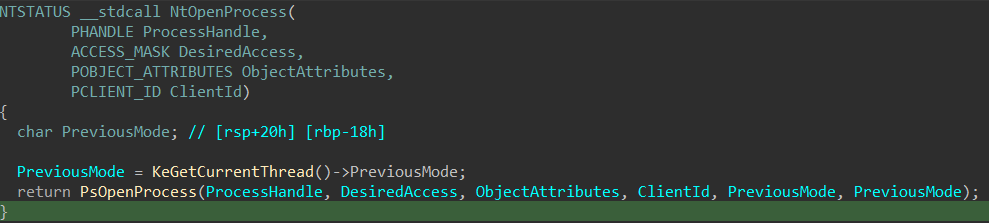

Let’s dive into how the PsOpenProcess function works internally. This function is called by the native API NtOpenProcess, which is used to open a handle to a process object. It resides in ntoskrnl.exe and is responsible for performing access checks, resolving the target process, and ultimately returning a valid handle.

NTSTATUS __fastcall PsOpenProcess(

PHANDLE outputHandlePtr,

ACCESS_MASK desiredAccess,

_OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES *objectAttributes,

_CLIENT_ID *ptr_ClientID,

char PreviousMode,

char AccessMode

);

The logic of PsOpenProcess can be broken down into four main steps:

- Check Object Attributes

- Locate the Target Process

- Perform Security Checks

- Create the Handle

PsOpenProcess Main Steps:

1. Check Object Attributes:

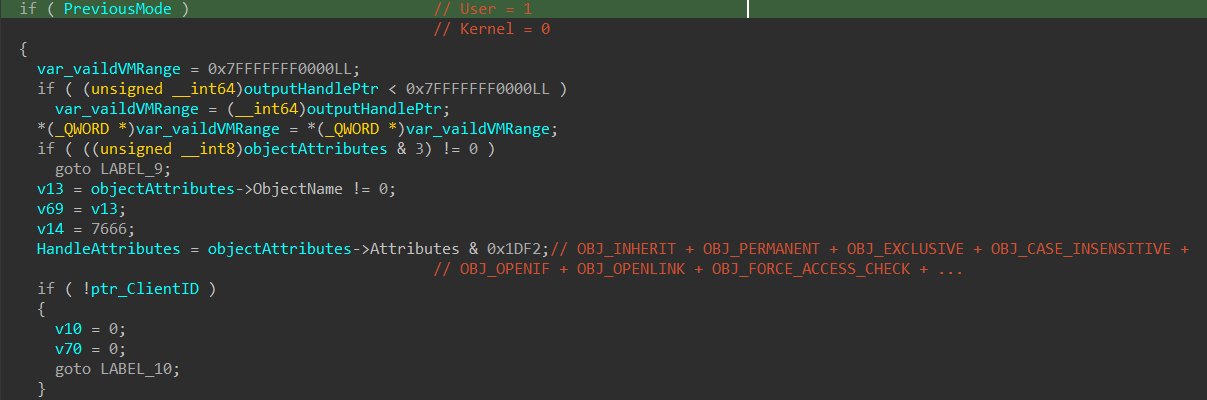

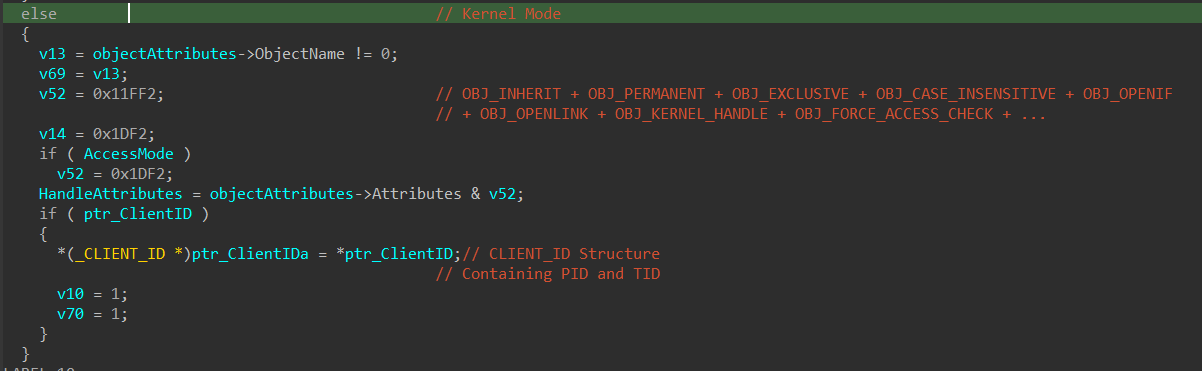

Starting from NtOpenProcess, the kernel retrieves the PreviousMode from the calling thread’s KTHREAD structure. This value determines whether the caller is running in user mode or kernel mode.

Based on PreviousMode, the kernel then validates the _OBJECT_ATTRIBUTES structure provided by the caller. This structure contains flags that define how the object should be treated.

#define OBJ_INHERIT 0x00000002L

#define OBJ_PERMANENT 0x00000010L

#define OBJ_EXCLUSIVE 0x00000020L

#define OBJ_CASE_INSENSITIVE 0x00000040L

#define OBJ_OPENIF 0x00000080L

#define OBJ_OPENLINK 0x00000100L

#define OBJ_KERNEL_HANDLE 0x00000200L

#define OBJ_FORCE_ACCESS_CHECK 0x00000400L

#define OBJ_IGNORE_IMPERSONATED_DEVICEMAP 0x00000800L

#define OBJ_VALID_ATTRIBUTES 0x00000FF2L

User Mode Callers: The kernel restricts allowed attributes to 0x1DF2 (disallowing OBJ_KERNEL_HANDLE).

Kernel Mode Callers: All flags, including OBJ_KERNEL_HANDLE, are allowed (0x11FF2).

2. Locate the Target Process:

The function uses the _CLIENT_ID structure to identify the target process. This structure contains both the process ID and the thread ID:

struct _CLIENT_ID

{

VOID* UniqueProcess; // PID

VOID* UniqueThread; // TID

};

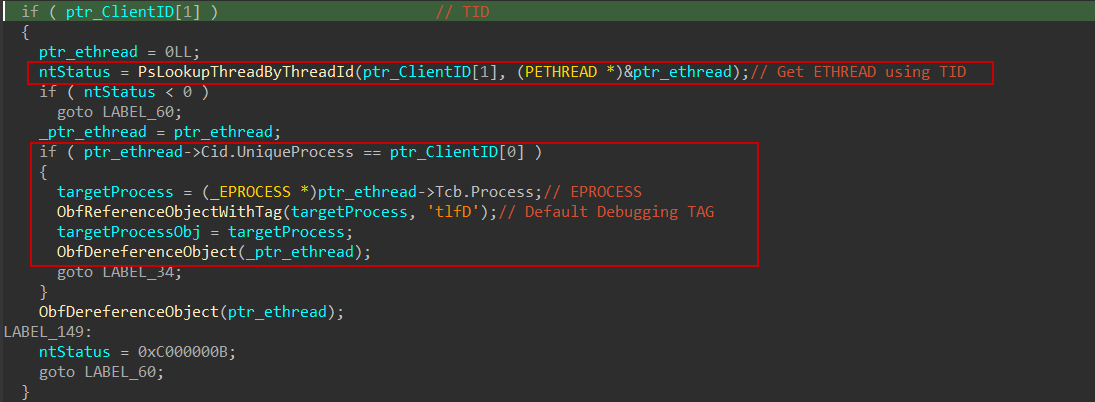

The kernel attempts to resolve the target process by first calling PsLookupThreadByThreadId using the thread ID (UniqueThread). If successful, it retrieves the corresponding _ETHREAD structure, then compares ethread->Cid.UniqueProcess with CLIENT_ID->UniqueProcess. If they match, it obtains the _EPROCESS structure for the target process.

To ensure the process object stays valid during access, the kernel then calls ObfReferenceObjectWithTag, which applies a 4-byte tag — I think it’s used for memory tracking or debugging purposes.

If the thread ID is not provided, the kernel takes an alternate route to locate the target process.

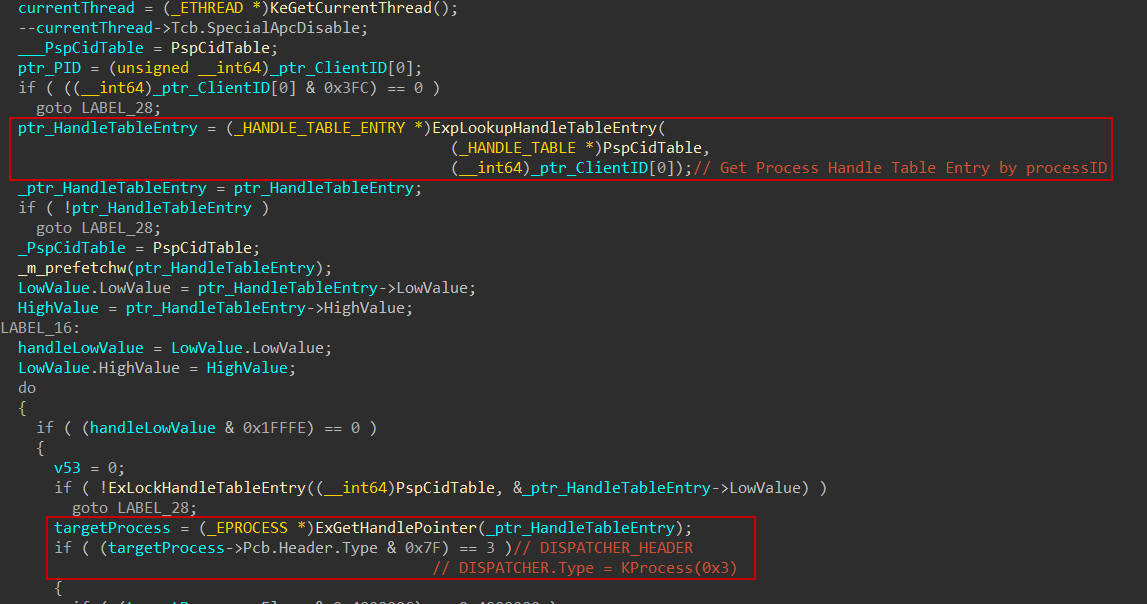

In this case, it attempts to retrieve the _EPROCESS structure directly from PspCidTable. According to Eversinc33, PspCidTable is a pointer to a system-wide handle table that contains entries for both processes and threads. This table serves as the underlying pool used by the kernel to manage and generate unique client identifiers (CIDs), including process IDs and thread IDs. Each entry maps a CID to its corresponding kernel object, making it a key component in object resolution when thread information is unavailable.

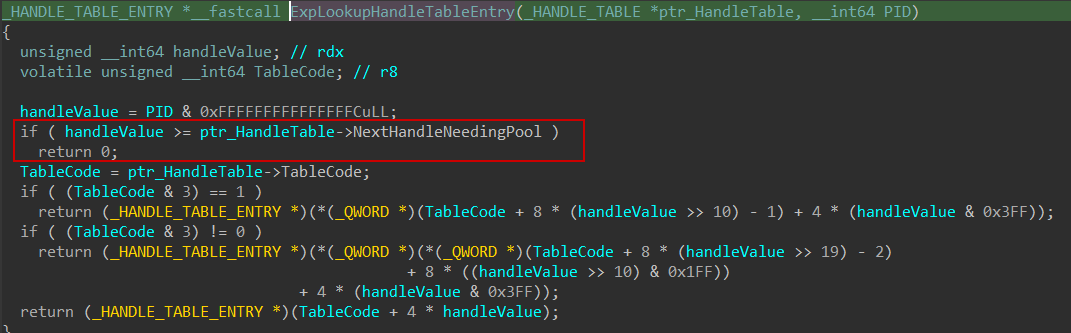

To achieve this, the system uses the undocumented function ExpLookupHandleTableEntry, which returns a pointer to a _HANDLE_TABLE_ENTRY corresponding to the provided PID value. Based on my observations, it appears that this function attempts to derive the handle table entry directly from the PID, as it checks whether the PID is greater than or equal to the NextHandleNeedingPool value. This supports the idea that the PID serves as the handle used to retrieve the entry from the handle table.

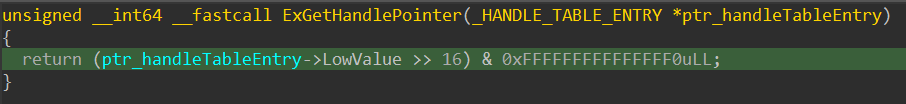

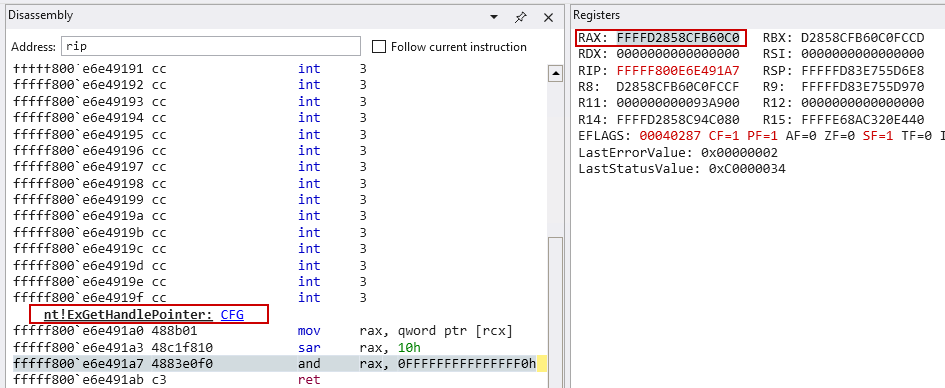

Then, using this entry, the actual object pointer is extracted via another undocumented function, ExGetHandlePointer (I think :D). This function retrieves the LowValue field from the handle table entry, shifts it right by 16 bits, and applies a mask of 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF0 to return the pointer to the actual object. It’s important to note that this yields a general object pointer—not necessarily a process object—since the handle could refer to any object type.

To validate my assumption, I confirmed that the object returned by ExGetHandlePointer is indeed a valid _EPROCESS structure. As shown below, the object contains expected fields, including a valid ImageFileName (“Notepad.exe”), which confirms that the retrieved object is a legitimate process structure. This observation confirms the idea that the purpose of ExGetHandlePointer is to retrieve a pointer to the actual kernel object.

kd> dt nt!_EPROCESS FFFFD2858CFB60C0

+0x000 Pcb : _KPROCESS

+0x1c8 ProcessLock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x1d0 UniqueProcessId : 0x00000000`000012b0 Void

+0x1d8 ActiveProcessLinks : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0xffffd285`8667b258 - 0xffffd285`86e25298 ]

+0x1e8 RundownProtect : _EX_RUNDOWN_REF

....................

+0x328 PageDirectoryPte : 0

+0x330 ImageFilePointer : 0xffffd285`8d26e760 _FILE_OBJECT

+0x338 ImageFileName : [15] "Notepad.exe" // => Valid process name

3. Perform Security Checks:

Before digging into the security checks, we need to understand some important structures that are used in the security checks.

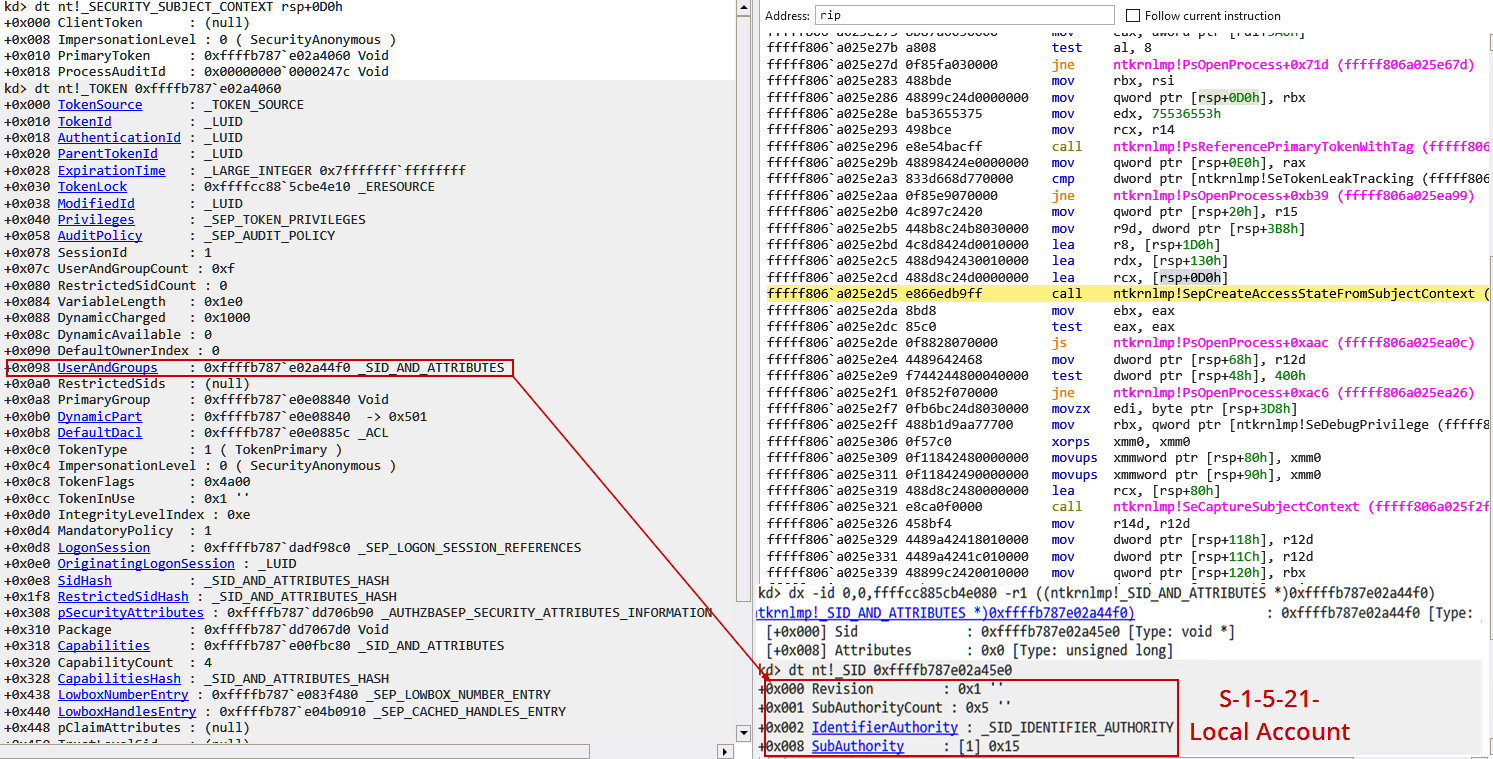

This structure is used to capture subject security context for access validation. One of its most important members is PrimaryToken, which is a pointer to a _TOKEN structure that holds the caller processs security attributes—such as the Security Identifier (SID), privileges, expiration time, and more.

typedef struct _SECURITY_SUBJECT_CONTEXT {

PACCESS_TOKEN ClientToken;

SECURITY_IMPERSONATION_LEVEL ImpersonationLevel;

PACCESS_TOKEN PrimaryToken;

PVOID ProcessAuditId;

} SECURITY_SUBJECT_CONTEXT, *PSECURITY_SUBJECT_CONTEXT;

It’s not documented that the primary token is a pointer to a _TOKEN structure, but I have confirmed that it’s a valid structure as shown below:

A security descriptor contains the security information associated with a securable object. It consists of a SECURITY_DESCRIPTOR structure and associated metadata. Two of its most important components are:

- DACL (Discretionary Access Control List): Contains Access Control Entries (ACEs) that explicitly allow or deny access to the object.

- SACL (System Access Control List): Contains ACEs that generate audit logs for access attempts to the object.

This structure is used to describes the state of an access in progress. It contains an object’s subject context, remaining desired access types, granted access types, and, optionally, a privilege set to indicate which privileges were used to permit the access. It will be used later in handle creation.

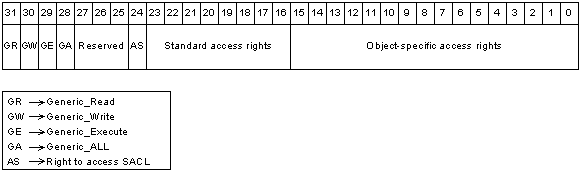

It’s a 32-bit value used to specify the access rights requested, granted, or audited for a securable object. It plays a central role in Windows access control mechanisms. This mask is typically composed of three parts:

-

Generic Access Rights: High-level, abstract permissions such as

GENERIC_READ,GENERIC_WRITE,GENERIC_EXECUTE, andGENERIC_ALL. These are translated (viaGENERIC_MAPPING) into object-specific access rights depending on the object type. - Standard Access Rights: Each type of securable object has a set of access rights that correspond to operations specific to that type of object such as:

DELETEREAD_CONTROLWRITE_DACWRITE_OWNERSYNCHRONIZE

- Object-Specific Access Rights: to determine the type of access to specific object:

- Process Objects:

PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATIONPROCESS_CREATE_THREADPROCESS_VM_READPROCESS_ALL_ACCESS

- File Objects:

FILE_READ_DATAFILE_WRITE_DATAFILE_EXECUTEFILE_ALL_ACCESS

- Process Objects:

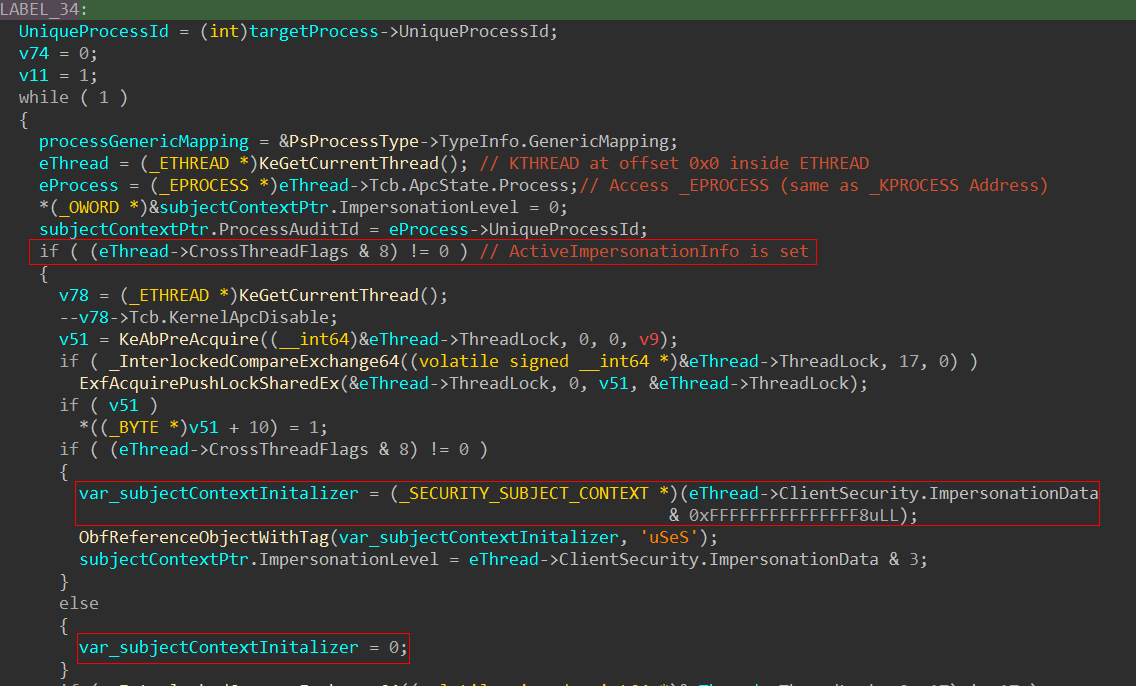

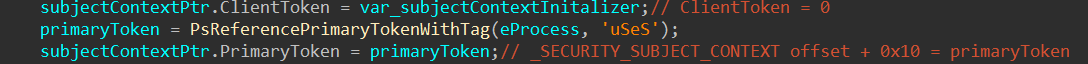

Back to our analysis, once the target process object is retrieved, the next step is to extract the SECURITY_SUBJECT_CONTEXT structure from it. To achieve this, the system checks for impersonation information in the caller’s thread by inspecting a bit in the CrossThreadFlags field. This bit corresponds to the ActiveImpersonationInfo flag, which, according to colinsenner’s research on HideThreadFromDebugger, indicates the presence of impersonation details. The goal here is to populate the SECURITY_SUBJECT_CONTEXT with the correct security attributes of the caller’s thread; if no impersonation info exists, the structure is zeroed out.

Next, the SECURITY_SUBJECT_CONTEXT structure is initialized by referencing the PrimaryToken of the caller process. This is done via the undocumented function PsReferencePrimaryTokenWithTag.

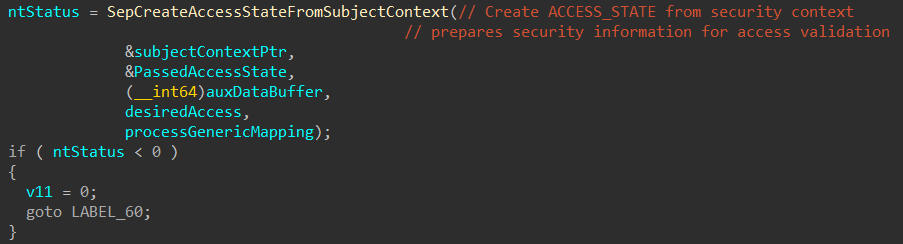

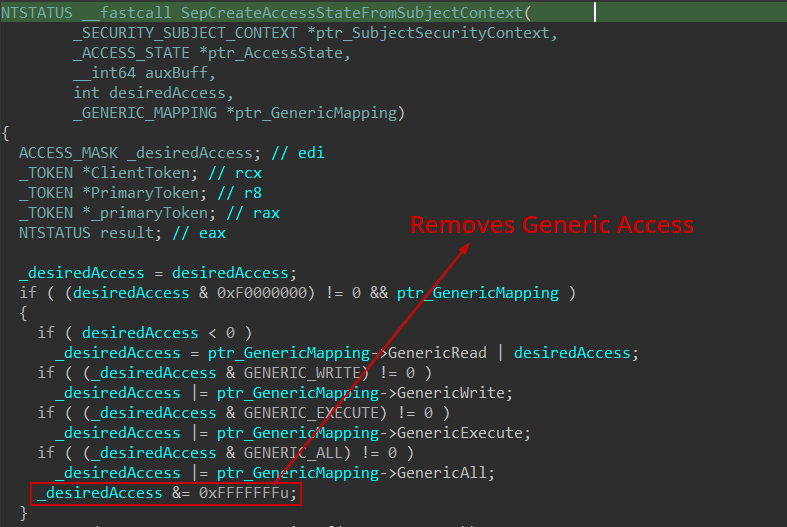

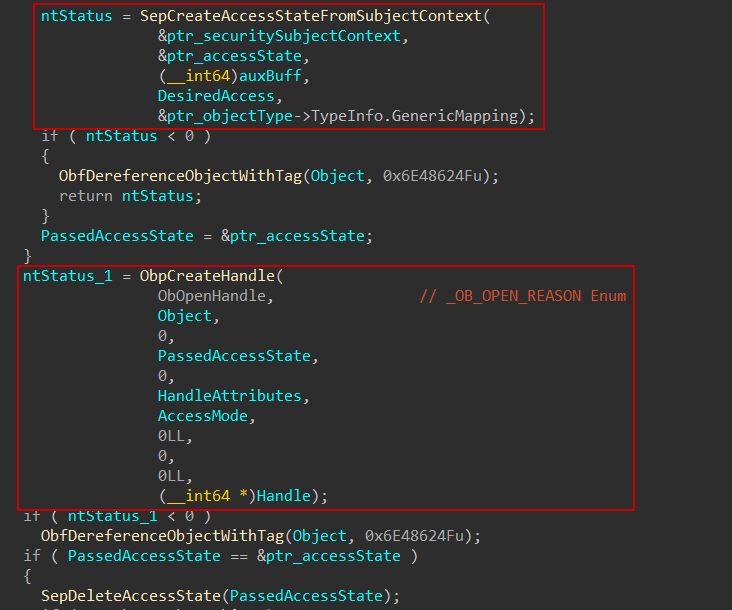

With a valid subject context in hand, a ACCESS_STATE structure is created using another undocumented function: SepCreateAccessStateFromSubjectContext which is actually used to initialize many fields inside such as:

- Object-Specific Access Rights

- RemainingDesiredAccess

- OriginalDesiredAccess

- AccessFlags

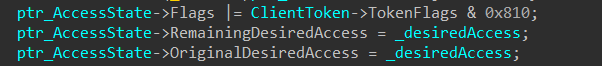

Following that, the function once again captures the SECURITY_SUBJECT_CONTEXT of the target process using SeCaptureSubjectContext. It then performs a privilege check using SepPrivilegeCheck to determine if the caller process has the SeDebugPrivilege enabled—provided the caller is executing in user mode. If the caller is running in kernel mode, the privilege check is skipped, and the privilege is assumed to be present.

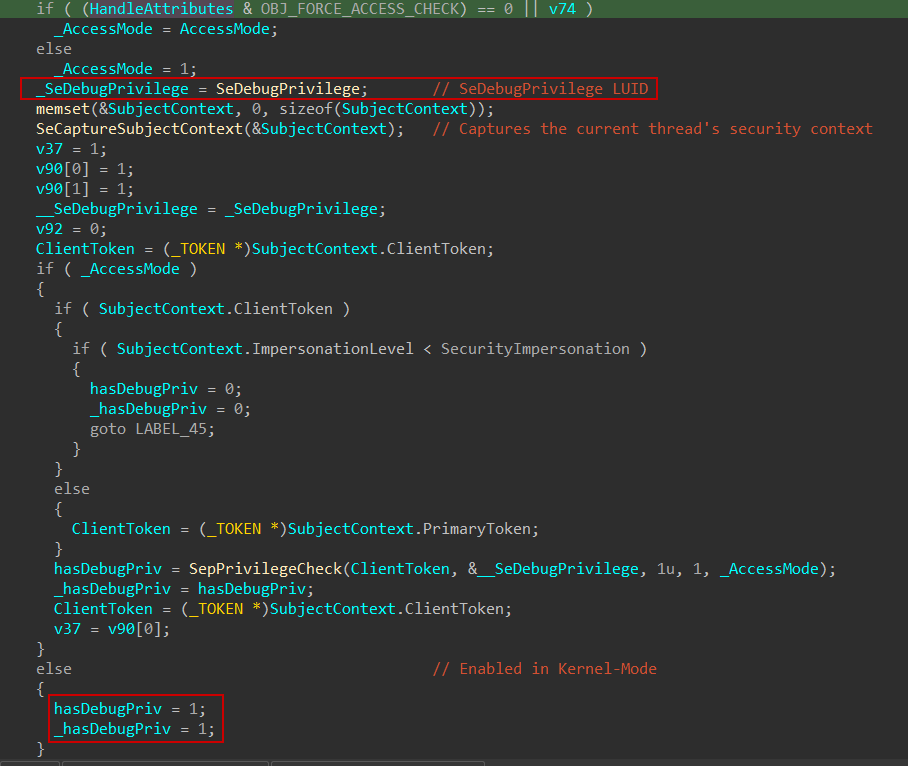

Then, it will retrieve the SID of the calling process. If the SID belongs to the LocalSystem, LocalService or NetworkService account, auditing is entirely bypassed. Otherwise, privilege filtering is applied. For all other accounts, including regular users and administrators, auditing is always performed using undocumented function SepAdtPrivilegedServiceAuditAlarm, resulting in the generation of Event ID 4673 whenever a privileged operation is invoked.

Back to the access state, Inside ACCESS_STATE there are 2 important members:

- PreviouslyGrantedAccess: This field holds the access rights that have already been granted to the caller so far during the access evaluation process.

- RemainingDesiredAccess: This field holds the access rights that the caller still wants but have not yet been granted — they are pending evaluation.

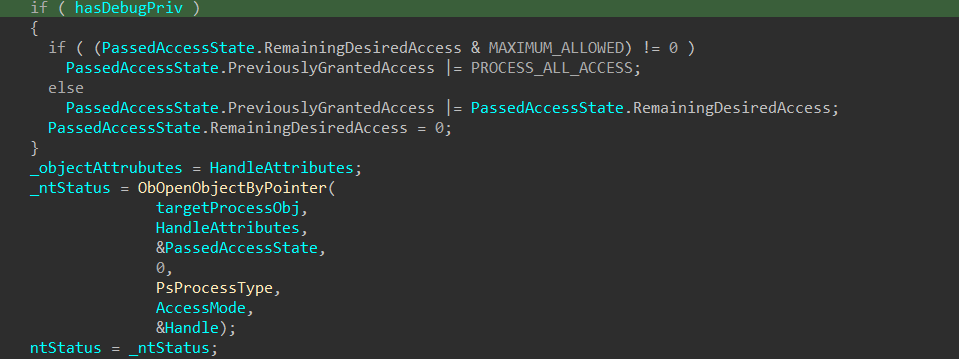

When the caller holds the SeDebugPrivilege, the kernel performs an elevated access check. If the RemainingDesiredAccess includes the MAXIMUM_ALLOWED flag (0x02000000), it grants full permissions by setting PreviouslyGrantedAccess to PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS. Otherwise, it grants the requested permissions by adding RemainingDesiredAccess to PreviouslyGrantedAccess. In both cases, RemainingDesiredAccess is then cleared (set to 0), indicating that no further access rights require evaluation. And finally call ObOpenObjectByPointer is mainly responsible for passing/creating the access state based on the desired access and the object type’s generic mapping to ObpCreateHandle which is responsible for object’s handle creation.

4. Create the Handle:

I’m not going to cover the handle creation process in detail, but I will focus on 3 main parts:

- Retrieve Handle Table

- Control Access

- Call Post-Object’s Callbacks

Retrieve Handle Table:

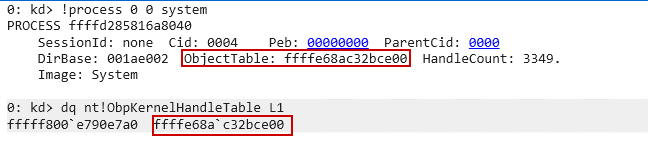

First, it examines the attributes provided by the caller for opening the target process. If the OBJ_KERNEL_HANDLE flag is present, the system uses the global kernel handle table (ObpKernelHandleTable) which is a global, system-wide handle table. Otherwise, it retrieves the target process’s own ObjectTable located at offset 0x300 within the EPROCESS structure.

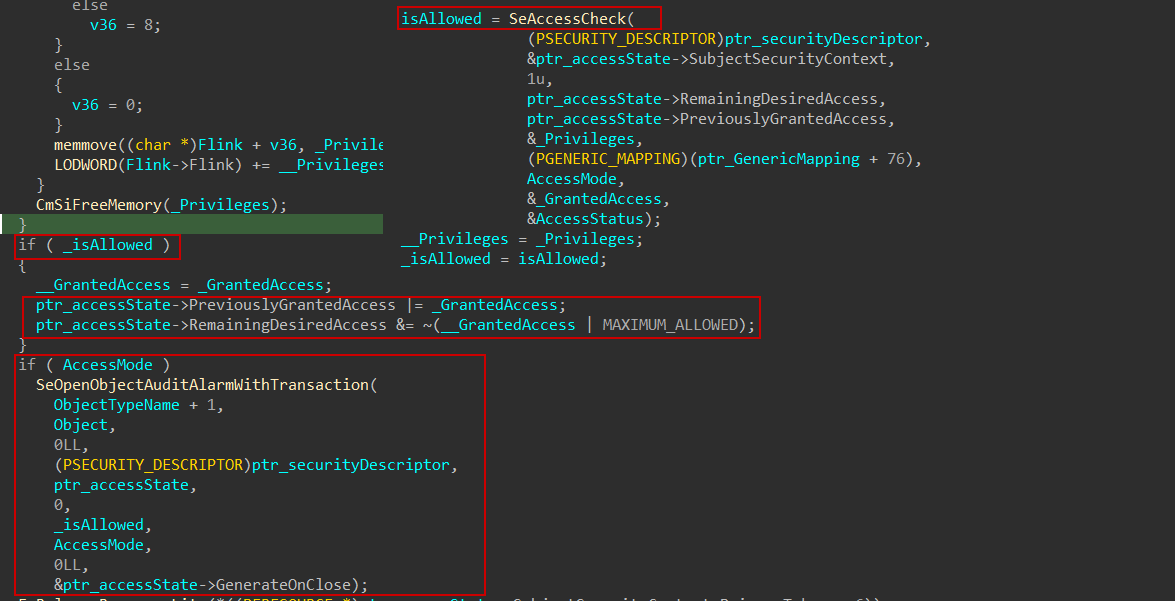

Control Access:

Then, it will use another documented function SeAccessCheck to determine whether the requested access rights can be granted to an object, based on its security descriptor and ownership information. If access is approved, the granted rights are stored in the PreviouslyGrantedAccess field, and the MAXIMUM_ALLOWED flag is cleared from RemainingDesiredAccess. After that, the system checks the caller’s access mode, and if it is running in user mode (AccessMode == 1), it calls undocumented function SeOpenObjectAuditAlarmWithTransaction which I think is used to raise an audit event corresponding to the access attempt.

Call Post-Object’s Callbacks:

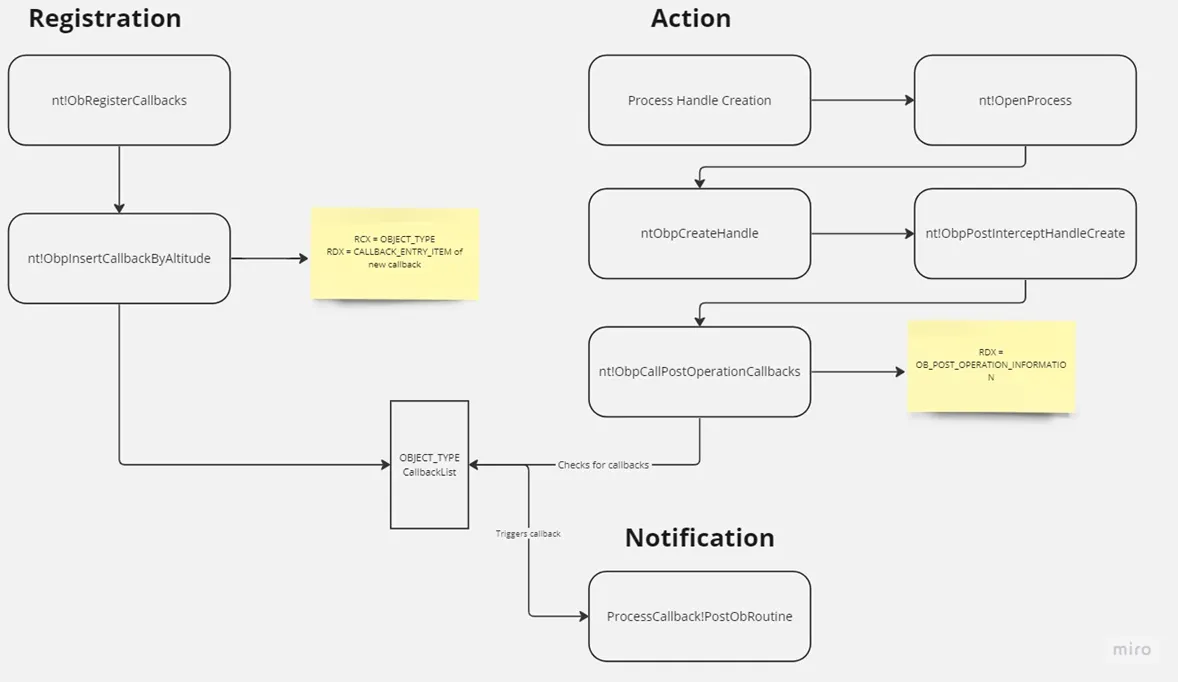

What is a callback? A callback in general is a routine that is triggered by an event. In the case of AV, it is a routine installed by AV engine to perform specific actions after/before any requested operation. When AV needs to install a callback, it will use the a well-documented function ObRegisterCallbacks to register it.

NTSTATUS ObRegisterCallbacks(

[in] POB_CALLBACK_REGISTRATION CallbackRegistration,

[out] PVOID *RegistrationHandle

);

The first parameter is a pointer to _OB_CALLBACK_REGISTRATION structure which specifies the list of callback routines and other registration information.

typedef struct _OB_CALLBACK_REGISTRATION {

USHORT Version;

USHORT OperationRegistrationCount;

UNICODE_STRING Altitude;

PVOID RegistrationContext;

OB_OPERATION_REGISTRATION *OperationRegistration;

} OB_CALLBACK_REGISTRATION, *POB_CALLBACK_REGISTRATION;

Inside it, there is another pointer to array of OB_OPERATION_REGISTRATION structures which specifies the pre and post operation callbacks and the operation type (Handle Creation, Handle Duplication)

typedef struct _OB_OPERATION_REGISTRATION {

POBJECT_TYPE *ObjectType;

OB_OPERATION Operations;

POB_PRE_OPERATION_CALLBACK PreOperation;

POB_POST_OPERATION_CALLBACK PostOperation;

} OB_OPERATION_REGISTRATION, *POB_OPERATION_REGISTRATION;

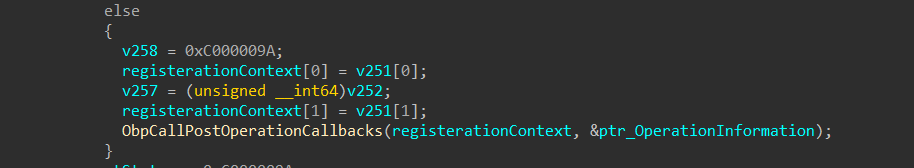

Returning to our analysis—during handle creation, the system invokes ObpCallPostOperationCallbacks, which is responsible for triggering any registered object manager post-operation callbacks. I’m not pretty sure about its arguments, it appears that the second argument (passed in RDX) is a pointer to _OB_POST_OPERATION_INFORMATION which contains details about the callback context. As shown in Figure 27, there are two additional functions not referenced in ObCreateHandle, which I suspect is due to differences across Windows versions.

I didn’t find any reference to ObpCallPreOperationCallbacks inside ObCreateHandle which is weird instead found in ObDuplicateObject

Debugger Access

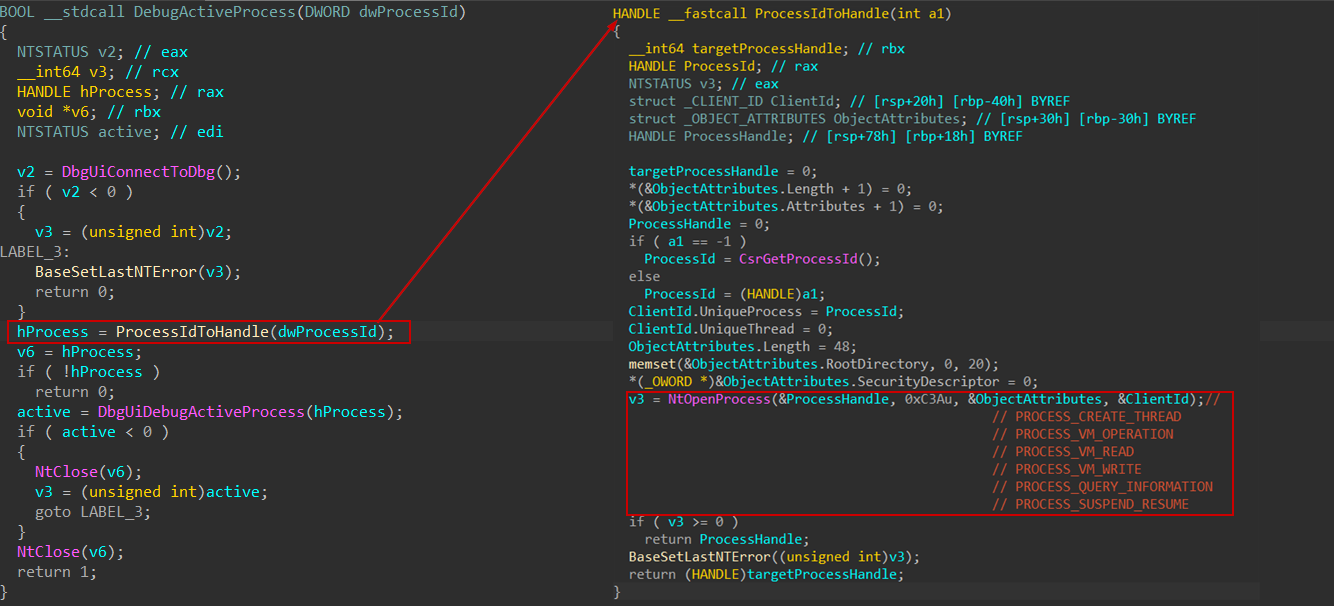

As Adams mentioned, the debugging process typically begins with a call to DebugActiveProcess, which instructs the debugger to attach to a target process by its PID.

DebugActiveProcess Under the Hood:

Internally, it invokes a helper function—commonly referred to as ProcessIdToHandle—which attempts to obtain a handle to the target process using its process ID. This involves calling the NtOpenProcess syscall with the following desired access mask: 0xC3A, which includes:

PROCESS_VM_OPERATIONPROCESS_VM_READPROCESS_VM_WRITEPROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATIONPROCESS_SUSPEND_RESUME

Kaspersky Internals: Callback Registration

To begin analyzing Kaspersky’s callbacks, we first need to identify where they are registered. This can be achieved through two primary methods:

- Using

WinObjEx64 - Using

PsProcessTypeObject

Locating Callbacks:

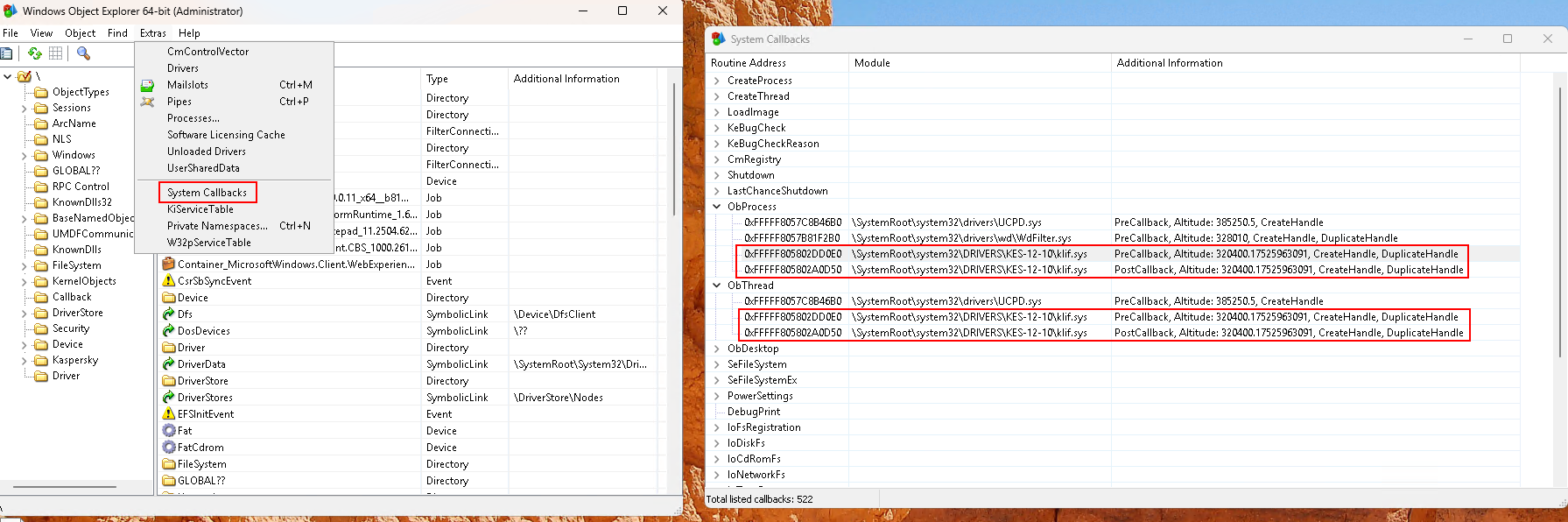

Using WinObjEx64:

We can enumerate the registered system callbacks, specifically those tied to handle creation and duplication events. As shown in the figure below, Kaspersky’s klif.sys driver registers both PreOperation and PostOperation callbacks. The pre-operation callback is located at RVA 0xD0E0, while the post-operation callback is at RVA 0x0D50.

Using PsProcessType Object:

All registered callbacks are linked through a list stored within the PsProcessType object at offset 0x0C8, which is a LIST_ENTRY structure. Each entry in this list points to a CALLBACK_ENTRY_ITEM, an undocumented structure that holds detailed information about each registered callback, including function pointers and callback types.

kd> dt nt!_OBJECT_TYPE poi(nt!PsProcessType)

+0x000 TypeList : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0xffff9689`016a37b0 - 0xffff9689`016a37b0 ]

+0x010 Name : _UNICODE_STRING "Process"

+0x020 DefaultObject : (null)

+0x028 Index : 0x8 ''

+0x02c TotalNumberOfObjects : 0xa0

+0x030 TotalNumberOfHandles : 0x75f

+0x034 HighWaterNumberOfObjects : 0xd3

+0x038 HighWaterNumberOfHandles : 0x779

+0x040 TypeInfo : _OBJECT_TYPE_INITIALIZER

+0x0b8 TypeLock : _EX_PUSH_LOCK

+0x0c0 Key : 0x636f7250

+0x0c8 CallbackList : _LIST_ENTRY [ 0xffffe58b`87979530 - 0xffffe58b`879d03c0 ]

+0x0d8 SeMandatoryLabelMask : 3

+0x0dc SeTrustConstraintMask : 0

While this structure is not officially documented, its layout has been reverse engineered and described by douggem as follows:

typedef struct _CALLBACK_ENTRY_ITEM {

LIST_ENTRY EntryItemList;

OB_OPERATION Operations;

CALLBACK_ENTRY* CallbackEntry;

POBJECT_TYPE ObjectType;

POB_PRE_OPERATION_CALLBACK PreOperation;

POB_POST_OPERATION_CALLBACK PostOperation;

__int64 unk;

}CALLBACK_ENTRY_ITEM, *PCALLBACK_ENTRY_ITEM;

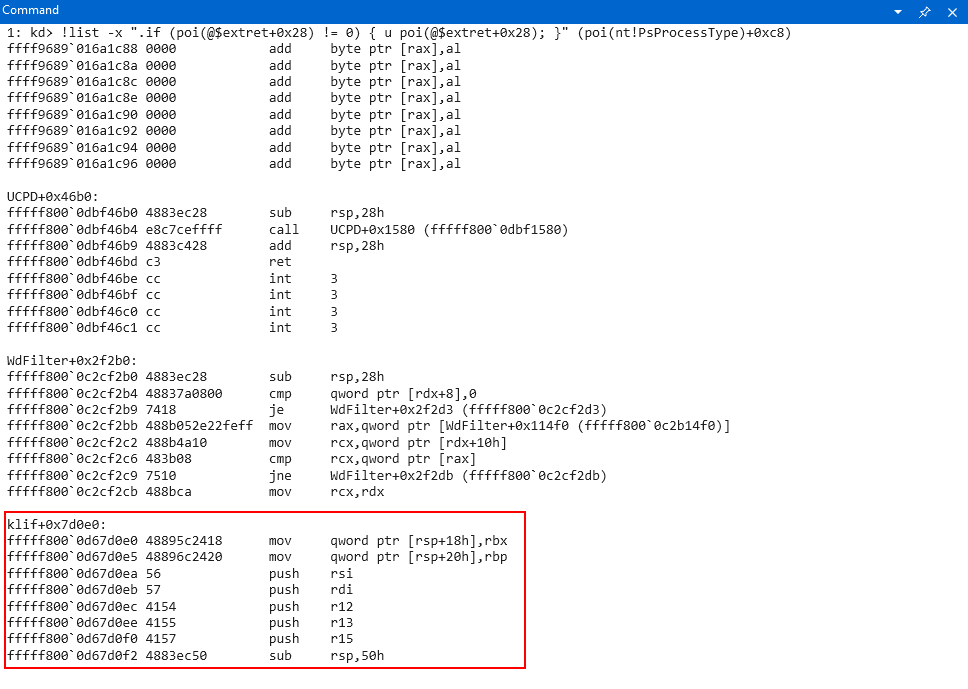

As adam said, we can iterate through the CallbackList to find the callbacks registered by Kaspersky. The following command iterates over each callback entry and disassembles its PreOperation function (located at offset 0x28 within the CALLBACK_ENTRY_ITEM structure):

kd> !list -x ".if (poi(@$extret+0x28) != 0) { u poi(@$extret+0x28); }" (poi(nt!PsProcessType)+0xc8)

Pre-Operation Callback

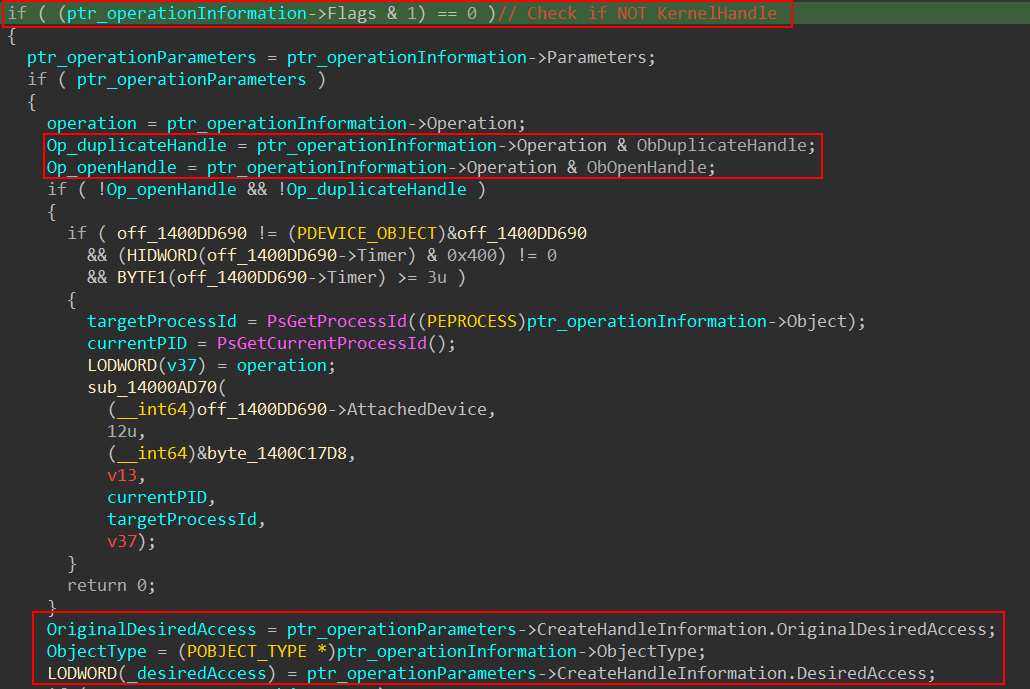

It receives one parameter which is a pointer to the _OB_PRE_OPERATION_INFORMATION structure. This structure is similar to _OB_POST_OPERATION_INFORMATION and contains critical details such as the type of operation being performed (e.g., handle creation or duplication), the object type, a pointer to the object itself, and the desired access rights.

The callback begins by checking whether the handle in question is a kernel handle. If it is, the function exits early by returning Zero. Next, it verifies the type of operation requested—either HandleOpen or HandleDuplicate—and retrieves the desired access rights for the associated object (e.g., process or thread).

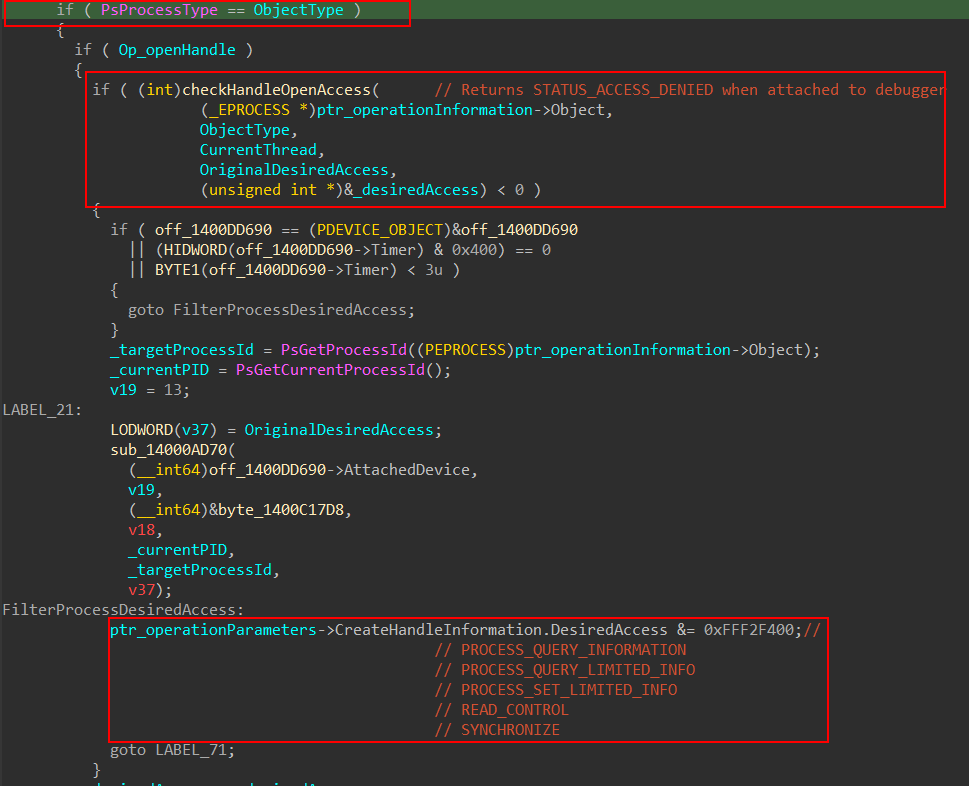

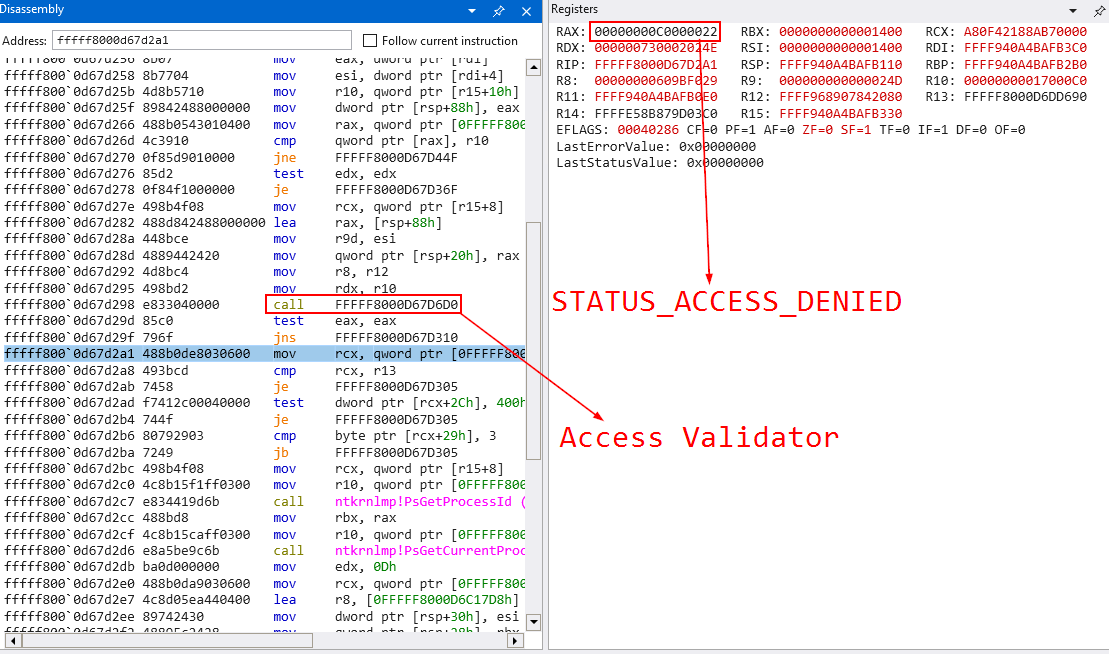

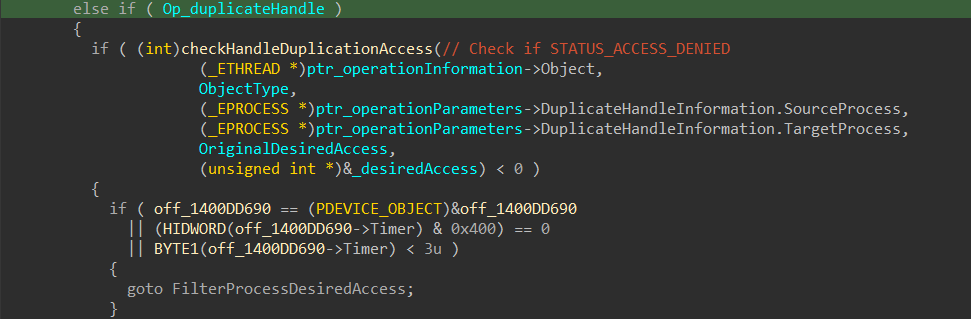

It then confirms that the object type is either PsProcessType or PsThreadType and performs a validation check on the requested access. If the validation fails with STATUS_ACCESS_DENIED, the callback proceeds to filter the access attempt. Only the following access rights are explicitly allowed:

PROCESS_QUERY_INFORMATIONPROCESS_QUERY_LIMITED_INFORMATIONPROCESS_SET_LIMITED_INFORMATIONREAD_CONTROLSYNCHRONIZE

The same access filtering logic is also applied when a handle is being duplicated, ensuring that only specific rights are permitted regardless of whether the operation is a handle open or duplication attempt.

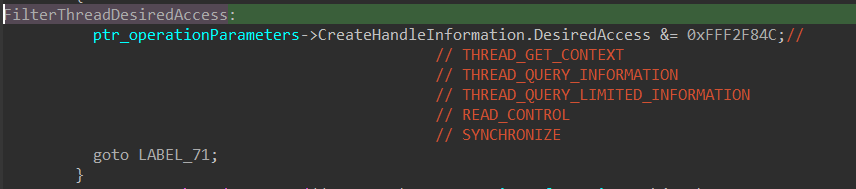

Similarly, the same access filtering logic is applied to thread objects. Only a limited set of access rights are permitted during handle operations, including:

THREAD_GET_CONTEXTTHREAD_QUERY_INFORMATIONTHREAD_QUERY_LIMITED_INFORMATIONREAD_CONTROLSYNCHRONIZE

Conclusion

In this post, I demonstrated how the Windows kernel manages handle creation through the internal workings of the PsOpenProcess function, breaking down its key stages—from object resolution to access validation and auditing. Additionally, we explored how Kaspersky’s klif.sys driver hooks into this process using pre-operation callbacks to enforce strict access filtering logic on process and thread handles.

References

[1] Reversing Windows Internals (Part 1) - Digging Into Handles, Callbacks & ObjectTypes

[2] Mastering Windows Access Control: Understanding SeDebugPrivilege

[3] Windows Anti-Debug techniques - OpenProcess filtering

[4] ObRegisterCallbacks and countermeasures

[5] libelevate - Bypass ObRegisterCallbacks via elevation

[6] Understanding Telemetry: Kernel Callbacks

[7] Journey Into the Object Manager Executive Subsystem: Handles

[8] ObReferenceObjectWithTag macro (wdm.h) - Windows drivers

[9] ReactOS: ExpLookupHandleTableEntry()

[11] PspCidTable Analysis

[12] (Anti-)Anti-Rootkit Techniques - Part II: Stomped Drivers and Hidden Threads

[14] SeAccessCheck function (wdm.h) - Windows drivers